The Joy Menu #34: Nightmare

Your author remembers that not all dreams are good.

Dear Creators,

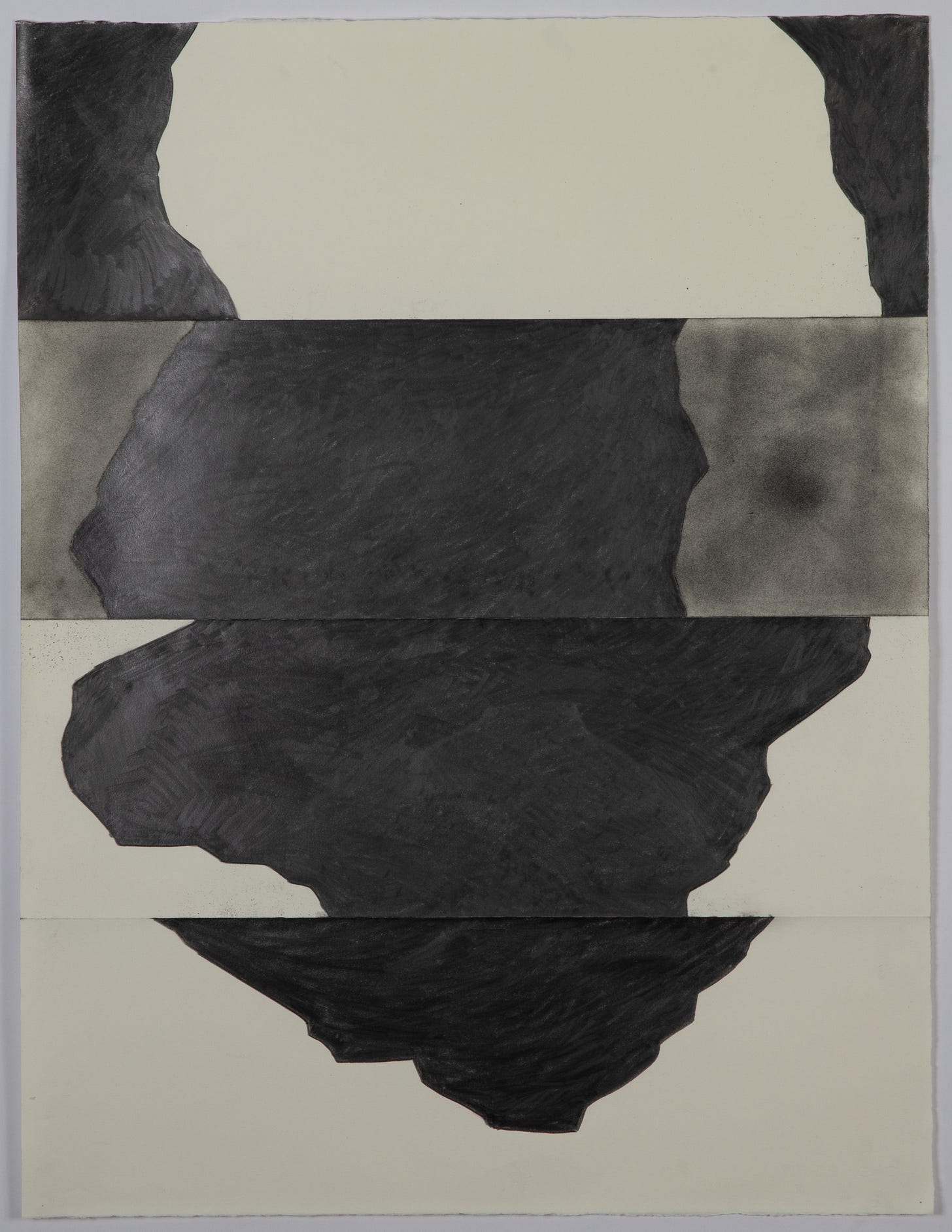

Last night I dreamed grief.

Not about grief, but grief itself; the feeling was the dream.

Like a child who wails so deeply no sound comes out, the dream was silent, and static. More than anything, it was a wanting, a knowing, a pain: a longing to touch and hold what’s never to be touched or held; a convulsion of lack with no salve; a dry and pulsing ache in the pit of the throat, the root of the chest.

There was a scene, but it seemed incidental: I was in a hotel room, or a bright, airy house. My mother and sister were there, but distant. I was alone, like a slap in the face: this was an unsolvable crisis; an unquenchable loss.

My father died three years ago. I did not think I had such a feeling, such a guttural, animal feeling, still heaving inside of me.

So that’s how healing goes.

Usually, I drive my grief around. I park it where I need it to be. I get out and do my business, while it waits in the car.

Last night, I woke, bound and gagged, inside of it. Under the hood. Inside the trunk. Inside the feeling.

March 28, 2018

He feels dizzy.

Tonight is the first night of Passover and my sister is having a Seder dinner out at the farm. Her siblings-in-law are coming, or some of them (there are many), a few of their kids – the ones young enough to still be around.

Here in Beachwood, at 9:30, a heavy pounding on the door. My mother, in her Minnie Mouse nightgown, scurries toward the back of the house, and my father, in his trademark tan shorts and an old black V-neck T-shirt, beelines for the door.

“How you doing today, sir,” a low, loud voice says when he opens.

“Fine, you?”

“Fine. Have a good day.”

“Thanks.”

Good days, I think, are hard with brand new chemotherapies pills, but such is the power of perfunctory neighborliness. The door closes and my mother, quickly, returns.

On the kitchen table they unpack the KoolTemp insulated container box and ask me if I can look at the paperwork. “I can’t do this now,” my father says as my mother hands me a glossy folder from the Specialty Pharmacy.

Inside, I flip through pages of redundant information: medicine disposal directions, lists of side effects (I skip looking at this one, frustrated that my eye catches even one word), payment liabilities, release forms. I sign my father’s signature two or three times, where it seems to be needed, and slip the rest back in the folder.

“It’s payment stuff,” I say.

“But we already paid,” my father says as he sits back down on his black leather Eames Chair (a lifelong desire we gave him as a 60th birthday present).

After some time, he says, quietly, as if to himself (but not to himself): “It doesn’t seem I’ll be going to Sarah’s tonight.”

My mom perks up, all eyes and pricked ears: “Oh?”

He says: “I’m feeling dizzy,” moves to the rocking chair, sighs.

Standing behind him, my mother asks: “Do you think you’re having a seizure?”

He shakes his head. “It’s just…fuzzy. Not right.”

I ask him to explain.

“Not dizzy,” he says and pantomimes a drunk clownish face: his eyes bugged, his hands waving next to his head, his body lurching back in the rocking chair. “It’s been in there growing like crazy with nothing to stop it. It’s been ten weeks since the medicine stopped doing anything, having a field day. I can feel it in there, doing its thing.”

The tumor is a thing. Not quite sentient, not quiet not. I think of horror films but they’re too cartoonish and easy to brush aside. This thing isn’t.

My father speaks in fragments or in paragraphs – nothing, it sometimes seems, in between. This a lot to say about how he feels, and I both want to ask more and want to change the subject fast. I also want to record it, but don’t want to grab for my phone in the middle of his description.

According to my sister, what he feels is more likely anxiety, or a shift in blood pressure, or at the most extreme small seizure-like symptoms (which may or may not be precursors to a bigger event coming). But this is not how it feels to my father. It is not how he is processing the experience. And as long as he is able to process and articulate what’s going on, I want to honor that.

My mother is frightened, I am sure he is too. Fear plays out in many physical ways. But he also has a tumor growing in his brain. How does that play out? Like this, it seems. Like however he says it does.

When does a dream become a nightmare? How? Is it rooted in an emotion you take with you to bed? Or formed of stray content loose in your subconscious mind?

As a kid, I dreamed night after night a single scene: I was at home with my mother and sister, and someone was banging on the door. It was rarely our actual house – sometimes it was, but often it was a dark, tan apartment, something I imagine being in the Upper East Side of New York.

My father was never home, and I was left to defend the household. Eventually, the door would break open, and then I knew we were done.

But the dream never ended; the worst case scenario never arrived. (The fear was in the tussle; the panicked attempt to batten the hatches, the convulsion of panic in feeling unsafe, unfortified, with my mother and sister but alone).

For how many nights of my actual childhood was my father not there – not tucked under a quilt, one leg looped over the comforter, yards away from my bed? Or laying next to me, his body rising and falling with hot, shallow breaths, woken by me and lured onto the futon?

Why did my subconscious require me to play out such scenes, as if this panicked rendering were likely, or possible, or heading my way?

I woke up this morning with a wave of calm. The feeling is loss, but the loss is concrete.

I am my father now. I lock the locks. I know when to answer the door.

It’s bewildering how little we really have to protect us. How little is really on our side. How much might be on the other side of the door. And how rarely it actually knocks.

Onward toward creative joy,

Joey