The Joy Menu #38: Catharsis

"Was it from that point that I began to hold the idea of 'being an artist' above all other pursuits and passions?"

Dear Creators,

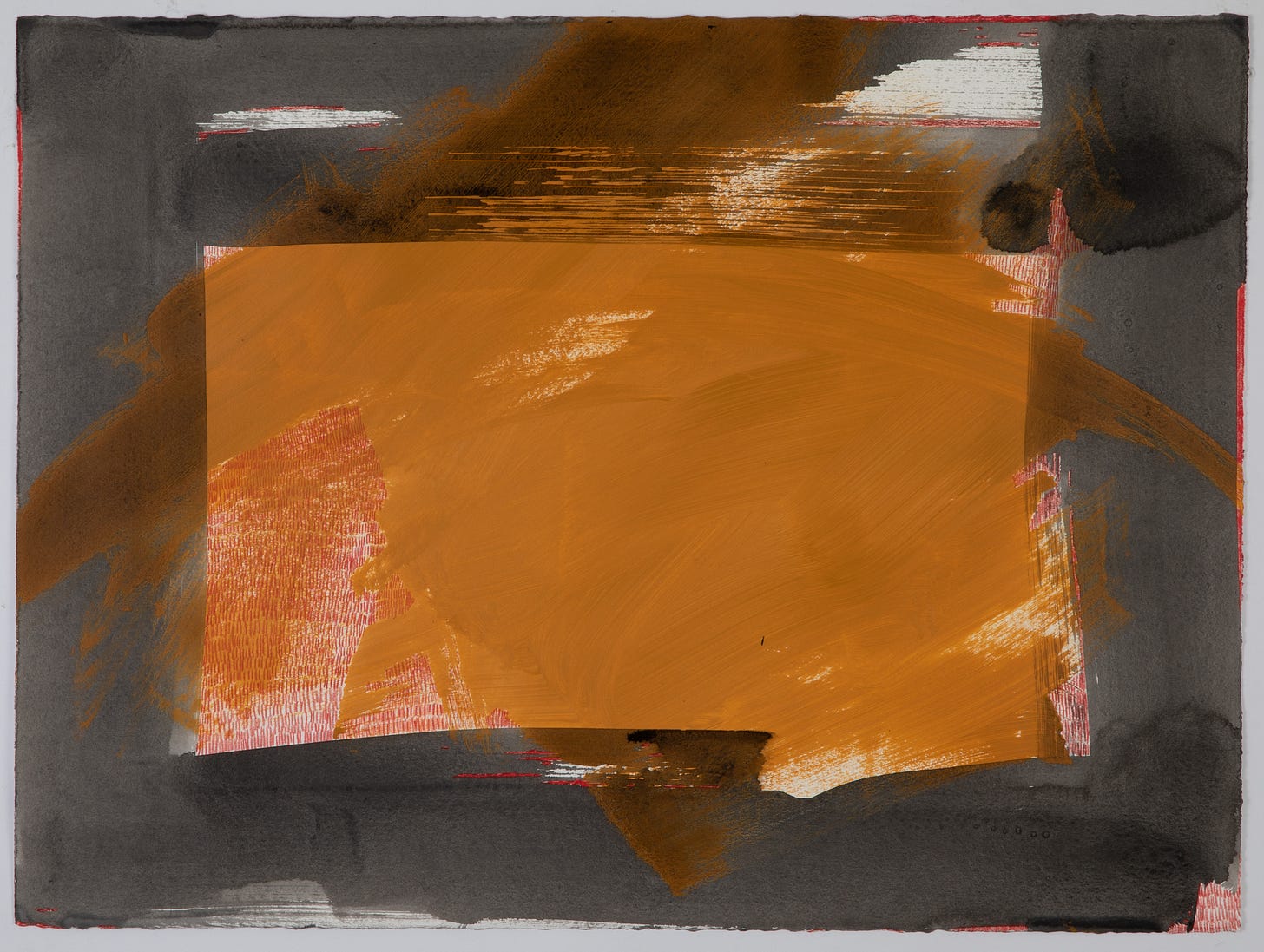

I don’t know when I first came to understand my father as an artist. I like to imagine I was eyeing one of the framed prints on the wall of our house, asking my mother where it had come from, or what it meant, and she replied: “That's your father’s.”

“My father’s?”

“Your father was an artist.”

More likely, someone pointed one out to me, or I overheard it said, apropos of nothing: “Alan made that one.”

Our home, a condominium — barely 1,000 square feet — didn’t have much wall space, but what we had was covered in art. His art, his friends’ art, trades he made for his colleagues’ or teachers’ art, the occasional piece gifted from his parents and carried around across the world.

I remember our world was filled with art, and the walls of our house were no different.

In the suburbs, the fathers I knew were contractors, doctors, lawyers, teachers, business men. So to know my father was an artist — that was incredible. I remember telling the kids at school about it, all the time.

It made me feel important. It made me feel unique. It explained some of the difference I felt in relation to my peers (all those children of doctors and lawyers and contractors); it cast a positive light on some of the discomfort I felt at being different.

I wasn’t just small and sensitive — my father was an artist.

Or had been.

I clung to that: to what he’d been — even though now he was a landscape architect, or a city planner, or sold micronutrient fertilizer from the bed of a Suburban, or was a construction manager.

It also explained him, to some degree, to me. The accent. The odd choice of pants. The tea. The beard (massively long before massive beards were a thing).

The fact that his art itself was abstract, and unlike anything they showed us at school, was somehow even more meaningful, though I couldn’t have articulated why or how.

Was it from that point, so early on, that I began to hold the idea of “being an artist” above all other pursuits and passions?

It certainly seemed more interesting than the lives lived by everyone around me. Even that of my actual, current father — worried about money, stressed by his commute, exhausted on weekends and evenings.

He never drew; he never painted; he never touched an instrument meant for creative, visual expression.

So always, from the first awareness of him as an artist, also, the question: Where did the artist go?

(I have fragmented memories, cherished and rare: seeing him doodle plans for a reorganized room, or a funny face on a grocery list, or a subtle shape on a note by the phone for my mom — each so rare they’re observed with wide-open eyes. The evenness of the pencil stroke, the confidence of each line, the delicacy of those mindless creations; a boldness and mastery evident even in the way he writes his name, belying years of training, and skill that can’t be erased.)

Art — like Africa, like Israel, like the army, like his travels, like his first marriage, like immigration — existed in him as part of the past we did not have access to: life before us, before our mother, before he was a bearded foreign man in the Orange County suburbs with a charming accent, short-shorts, and a predilection for toasted bread with jam and cheddar cheese on top.

I ask my mother, but never him: What made him give up art? What convinced him to leave it behind so completely? Why didn’t he continue part-time, as a hobby, just a little bit?

Why did I never ask him?

When I complain of having lost the urge, my lack of motivation, my disinterest in achieving my own artistic goals, Nick asks: “So what is beneath them?”

Writing is an act, an artful act, but what intention, what desire, what need, what purpose, lies behind it, beneath it; fuel or groundwater or true motivation — beyond ego gratification, beyond pats on the back, beyond (small) profits or (modest) awards?

What human itch does this artistic need scratch?

Was I called to art because it made me different? Or because it made him different?

Or was there something else?

I came to understand that my father stopped creating because he found himself in his mid-thirties, with two kids and a third on the way.

So I never had kids.

I came to understood that he hadn’t been making money, that he’d lost interest in the grind of “being an artist;” in trying to sell, in the hustle, in trying to make art of the hustle, in trying to make the hustle itself into an art (and all without the guarantee of success).

So I tried to do nothing else but art, and then something else besides art.

Neither brought me joy.

With the exception of small moments and casual sketches, I didn’t see my dad make art until after he was retired, and then mostly after he was sick. Yet I did see him, through most of my life, entrusting his emotional life into the hands of art, into the experience of art: music (constantly), museums (monthly), performances (whenever a great artist came through town), movies (two or more every weekend).

I saw his tears at the most poignant moments. I read the calm on his face after each catharsis.

Was my aim to provide catharsis? To him? To myself?

Was there ever a difference?

All I knew was that I was full of feelings, and art was a way to express those feelings.

Either to express them, or to make them matter.

Either make them matter, or just to get them out.

Not just pain, but clarity. Not just clarify, but community. Not just community, but catharsis.

“If I can get this into a song, onto the page, then perhaps…it will feel good, or it will mean something, or it will matter, or I will matter…”

Like trying to run in a dream.

Like trying to rescue a cat from a burning building.

It took us a decade to buy a Nintendo, and two to buy a house, but we saw Rostropovich and Yo-Yo Ma, Alvin Ailey, and Martha Graham, the LA Philharmonic, the Boston Pops, Poncho Sanchez and Ladysmith Black Mambazo, a thousand movies, and every museum exhibit we could drive to on the West Coast.

After food, a roof, and our studies (which included so many music lessons), we had art.

So how much of this urge is nature — inherited through his inheritance, built into the very molecules that make my beard bushy and my deep-set eyes green?

And how much is nurture — modeled by his values, his actions, his suggestions, taught to me the way a child learns best, with immersion, with experience, with love?

And does it matter?

Onward, friends, toward your creative joy,

Joey