The Joy Menu #39: Letters

"For most of my life, it's all I knew of that time, the last chapter of my father’s boyhood."

Dear Creators,

In my late 20s, when I was living back at home under a cloud of disappointment and frustration, my father discovered the world’s greatest raisins.

A market had opened nearby which exclusively sold nuts and dried fruit imported from Iran. Every week, he brought home bags and bags and different treats: fat, crispy almonds, cashews like crescent moons, melon seeds roasted in lime, squash seeds coated with chunky sea salt. And then among them, golden raisins of such deliciousness that we were both stunned by their perfection.

For days, we ate fistfuls together and nodded.

My father told me that in all his years living in Africa, in Israel, in California, traveling through France, Italy, Greece, the Middle East, he’d never had a raisin that good. I couldn’t argue.

I’d never had a thing against raisins, but neither would I have listed them as a favorite food, or even a preferred treat. They were just...raisins. Unexotic. Tart. Chewy. Appropriate when thrown in trail mix, or added to a bland cereal, or chucked on top of peanut butter, but otherwise uneventful. Boring, even.

These raisins were different. The texture was snappy and pert, the flavor pure and bracing. They had a sweetness I’d never known — inviting and pushy. And a mouth feel of which we never seemed to tire: firm and interesting, alluring and surprising, and also, somehow, correct.

We looked at each other, chewed behind smiles, and marveled.

“These are amazing.”

“These are wild.”

“These are so good.”

“We have to get more.”

Yet when my father returned to the store in the following weeks, and then months, those raisins were never again in stock.

They were a one-time thing. A one-time perfection.

In the summer of 1968, my father set out from Israel — a country he’d lived in, at that point, for 3 years — to travel around Europe with his older brother, Cliff, and his best friend Maurice. He was about to turn 18.

It was June when he left Tel Aviv for Paris, and it would be August when he returned to Tel Aviv from London. By September, he’d registered for military duty, and by October he’d be basic-trained and awaiting deployment.

For most of my life, that’s all I knew of this time, the last chapter of my father’s boyhood.

Despite the variety of experiences he had in his life — being twice an immigrant before age 25, having lived in a three countries, and a half dozen cities, visited countless more with uncertain status, worked two dozen odd, menial, and interesting jobs, having served as a military chauffeur, and then a sentence in a military jail for refusing to return as a reserve driver in the West Bank, having studied art in Tel Aviv, and in Chicago, and in New York, having painted (art and houses), planted (roots and gardens), spoken (English and Hebrew), and enacted a litany of other wild, mundane, unusual, common and unknown versions of himself — my father was not a storyteller.

He was a story consumer, a great reader and movie-watcher, who cried easily and had a quick, all-consuming wheezy laugh (which was bliss to evoke) when you told him a story he liked (and he always liked a story told to him by his children — especially if it was about his children).

But most of what we knew about him we picked up in bits and fragments.

My father used to say that there were two types of immigrants: those that live stuck in the past, backward and nostalgic, and those who get on with life in their new home, who look forward and live where they are.

It was never unclear which type of immigrant he felt himself to be, and it was never unclear which type he preferred to be.

Nostalgic conversations about Israel with Israelis boiled his blood, as did any romanticization of South Africa, even (or especially) by family members remembering happier times — even if (or especially if) they were personal memories, childhood memories, memories he might have shared.

I always suspected there was pain there; a wound he didn’t want to re-open. But he would have rolled his eyes at this, pursed his lips, and said, “Bullshit.”

I came to understand his trip through Europe as an exploration of alternate life paths, or places he might live; as a chance to explore the feeling or feelings surrounding emigration; and a way to spend time with his older brother — as they’d been apart the last three years, while my father did high school in Israel, and his brother finished his own military service in South Africa.

The question I understood the trip to be asking was: would he return to Israel to serve in the army (and be near his family), or emigrate to Europe, or America, or elsewhere, or would he head back to South Africa, a place he’d only just left, despite its continued problems, and his questionable place there?

I could not have ever know this for certain. What I knew, or thought I knew, I picked up from suggestions, elisions and assumptions.

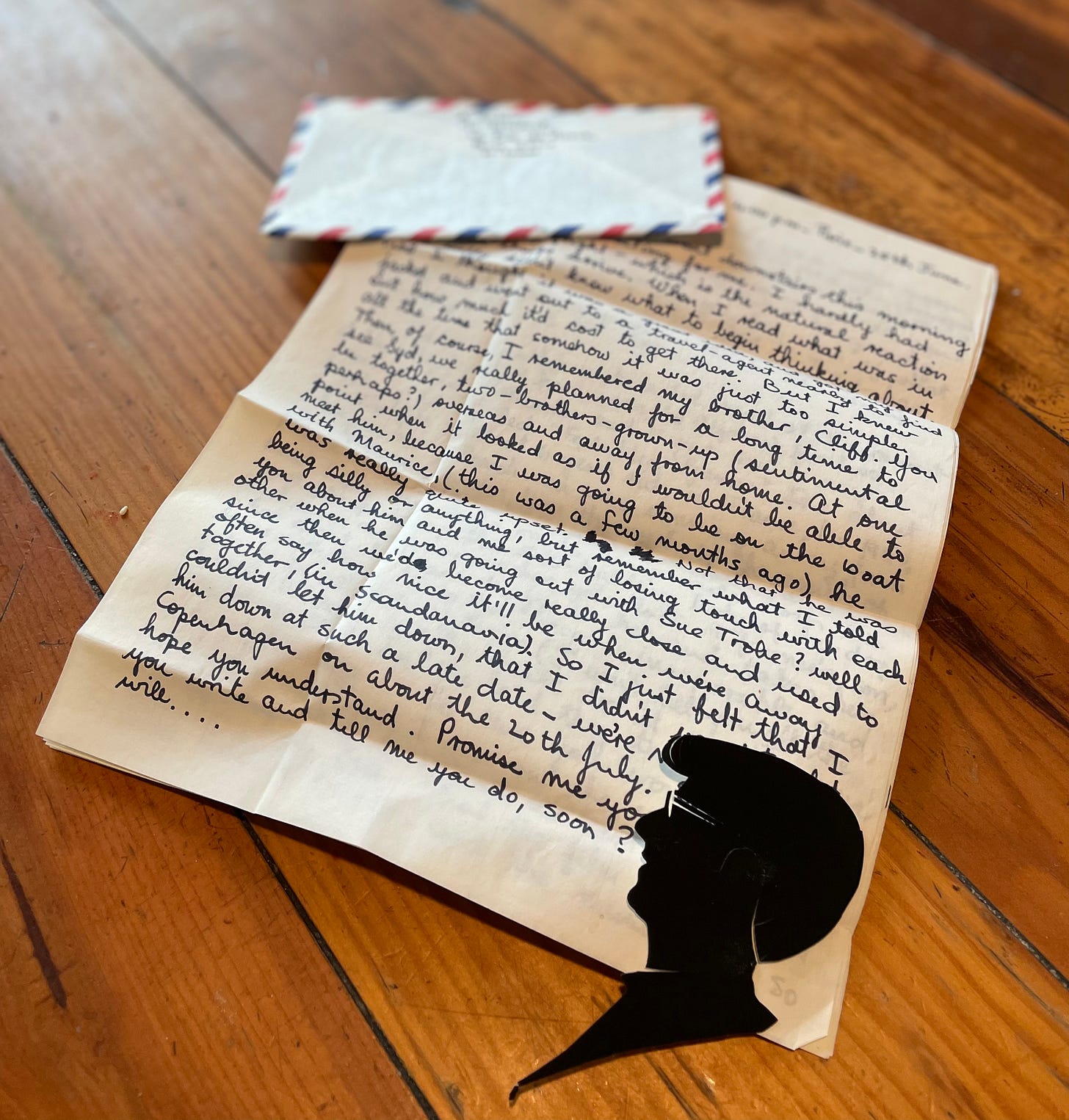

And then one day, weeks after his diagnosis, before he and my mother began to sort through their lives in anticipation of leaving for Ohio (where she would live, and he would die), he handed me a soft, white envelope filled with old airmailed letters.

“I thought you might enjoy these,” he said. “They’re from when I was a kid.”

I took them, stunned, and hid them away.

It turned out that a few years before, he’d found himself back in touch with an old friend and she had sent him nineteen letters he’d written to her in the summer of 1968. Nineteen letters sent from Paris and Antibes. From Copenhagen and Upsala. From London and Trondheim and Tel Aviv.

Nineteen time capsules in my father’s eighteen year-old hand. Nineteen letters from a version of my father lost to time — which I now held in mine.

My plan immediately became that I would travel to the places where each letter had been written, and read them there, near where he may have sat, where he may have breathed, where he may have written.

To reconnect to where he’d last been a boy and so long ago started out as a man. To seek to discover a version of him that I could never have known, and could only just begin to recapture or understand.

The one-time thing; the one-time perfection.

It sounded beautiful. An act ripe for narrative richness and worthy of Elizabeth Gilbert.

And then there was a global pandemic.

I know more about my father now, after having lost him, and thought about him, and written about him every week for so long. I’ve been waiting for the pandemic to end to take the trip.

But patience has never been my strongest virtue. I may start reading them soon.

You’re invited to join me, if you’d like.

Onward toward creative joy,

Joey