The Joy Menu #68: Cello

In a way, while the sale was open, while the cello remained unsold, part of my father remained alive. Far from view, over the crest of the horizon, but alive.

Dear Creators,

Again, another way, my father calls.

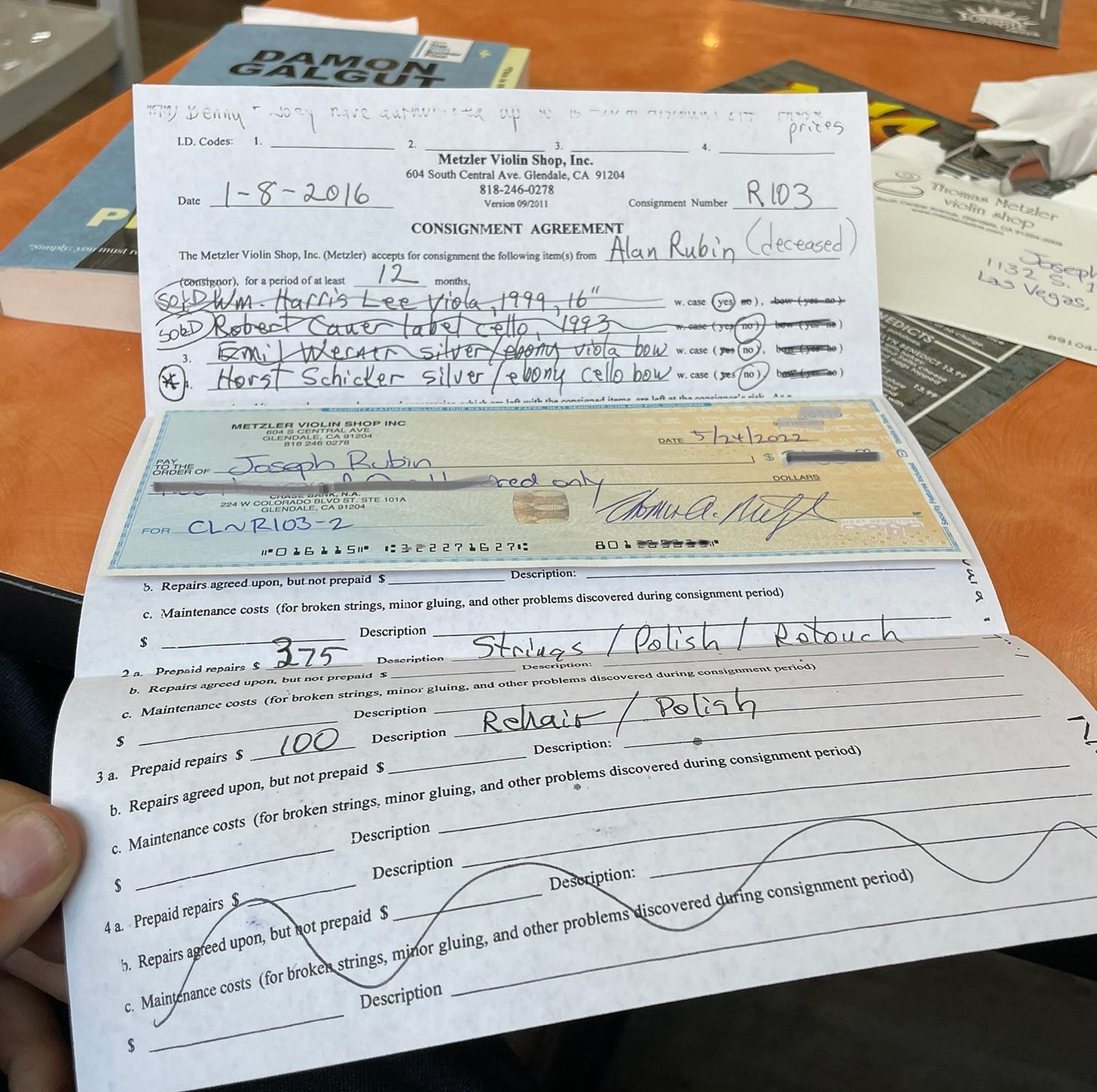

The cello that he dropped off at a violin shop in Los Angeles has finally sold.

The shop worker, Wesley, is asking for a forwarding address so he can send me a check for our share of the sale. He has a few addresses on file: one in California where we used to live; one in Ohio where my father and mother moved after my dad got sick; and one in New York, where he sent the money paid out to my brother, for his own instrument sold some time before in a similar sale.

After I give him my newest address, he thanks me and says, “I guess this closes up our account with your father.”

I flinch. I want to protest. “No, no. Don’t close it. You never know.” Though I do.

In a way, while the sale was open, while the cello remained unsold, part of my father remained alive. Far from view, over the crest of the horizon, but alive.

His drive to LA (he did it every day for work, but this drive had a different purpose, into a different part of town), his visit to the shop (he smells the wood, the rosin, the horsehair, remembers his own love of our playing), his decision to let them restring and clean the instruments, to deduct that cost from the sale (how he loves to spend money on something worthwhile), his request that they forward whatever profit is made on to his sons (this type of generosity his deepest instinct)—all of that is him living. And the result (the sale, the call, the need for a forwarding address) are direct results of actions he made that day, when he walked into the crowded shop (hear the bells jangle as he presses the glass door open, see the violin maker look up over his glasses) in shorts and New Balance sneakers, or dressed in black jeans and his black Rockport “work” clothes.

So when the check arrives—with a dated list of all the instruments, bows, cases ever brought in on his account, each crossed off and dated with when it was finally sold—I hesitate to cash it.

On the line labeled “Customer” I see my father’s name, and next to it, written in a different ink, lighter: the word “Deceased.” This feels overly final, fraudulent; he shouldn’t be dead to Wesley.

I wonder who told them. Did my brother call to update the account? My mother? Did I?

Part of me thinks my father did it himself—and not just because he was aggressively gleeful about sharing his impending demise toward the end of his run. Or maybe Wesley just sensed it. It can take so long to sell a stringed instrument, such customer transitions could be routine.

Eventually, I cash the check. Generosity with money was one of the main ways my father expressed love, and he doesn’t have many opportunities to express it directly these days. And despite the feeling of openness the telephone call inspires, there is no way to call my father back. These days, all his phone calls are one-way.

The Cello Suites

In Pablo Casals version, he opens with a lilting dance. A younger sound, despite the tinny tone from the old recording, and the static which mars each note with a slight subterranean drone, a dry yet even undercurrent beneath the near-syncopated wobble of his melody.

For Jacqueline du Pré, the opening is solemn, a slow walk by a frozen lake. The quarter notes drag and there’s a choppy yet laconic draw of the bow for each, which you can hear with distinctive motion as she changes direction. Somehow, while beautifully articulated, each note also feels stuck; a tear which does not want to be cried.

While he plays the same notes, Yo-Yo Ma’s tune is almost jaunty, contented—a middle aged man reflecting on a life well-lived. The tones which du Pré dragged flutter for him; those that lilted for Casals loft instead. They hop, each like a foot on a step descending downward, heading toward a doorbell which has just been rung.

Rostropovich, however, hurries through each line; it’s as though he doesn’t have time to waste with dances, or emotions, skill, or satisfaction. His proceeds with the gruff reliability of a march: each note the same size, the same shape, the same weight, each moving by quickly to make room for the next.

I could go on—or I could have at one point.

How many Saturdays began with the sounds of Bach’s Cello Suites soaring through the house? My father making tea, or sitting in concentration on his chair, or wandering the house whistling the unadorned melody to himself?

As I was a kid, I preferred Rostropovich. Perhaps because we’d seen him play once (I’ll never forget his bent end-pin, his closed eyes and blank brow).

As a teenager, I switched to du Pré. Perhaps stirred by the tragic aspect, the fact that she’d been forced by illness to stop playing at 28, and had died at 42.

(How many times did we join him on the couch to watch her perform “The Trout,” or the Dvorak or Elgar concertos; I see her now filling our tiny TV with a stirring vibrancy, a wild intensity, held forever in a energetic blond explosion—a youthfulness which we still then embodied ourselves.)

As a kid, I wondered how I would play Bach’s suites if I ever got good enough to learn the cycle. “I’ll give you a thousand dollars if you do,” my father would say.

I never took him up on the offer, nor took it seriously—though he did buy me the sheet music at one point, and I did learn the opening bars. To have really done it justice would have required a year of study or more, even just to play them poorly, and that would have been practicing four or five hours a day. And who wants to study relentlessly only to play something poorly?

Especially notes which hold such power; the most famous emitted by the instrument I called my own.

I bought the cello when I was 13, with the money I was given for my Bar Mitzvah.

For years, I pulled it behind me in its oversized hard case—like a young undertaker carrying my own coffin. I brought it every day to high school. I packed it into my dorm room at college.

Often, people seeing me with the case would say, “I love the way a cello sounds,” or, “the cello is the most beautiful instrument.”

But ask the partisan what he loves about his flag and I guarantee it’s not the colors or the pattern—it’s more emotional: the experience of ownership and belonging.

The cello was this for me. Unlike sports which I played, the cello played me—it became my calling card, my personality, my conduit to friendships and connections, as much part of me as my mouth or name or blood.

And like my father‘s accent, I could only hear its uniqueness, its quality, its beauty, when others would point it out.

Perhaps to interpret Bach’s suites—what Rostropovich saw as a march; du Pré played as an elegy; Ma sang as a conquest—would be to shift my relationship to that instrument from one of identity to one of artistry.

From one of meaningfulness to one of meaning-making.

And what could I add to the sounds of the world’s greatest cellists?

And what could I add to the sound of my father’s voice, to his fading accent, to his calls which keep coming from beyond?

Onward to creative joy,

Joey

"And despite the feeling of openness the telephone call inspires, there is no way to call my father back. These days, all his phone calls are one-way."

"Somehow, while beautifully articulated, each note also feels stuck; a tear which does not want to be cried."